Private Equity and Climate Change: Now the Work Begins

Never miss a thing.

Sign up to receive our Tax News Brief newsletter.

If the United States and other countries must invest trillions of dollars in energy transition to avoid a climate crisis, can traditional capitalism get the job done? Most western business and political leaders strongly prefer market-based over government-based allocation of capital. And that depends on returns. If private equity activity in the energy transition arena is any indication, returns will require hard work, persistence and commitment to long term success.

Private equity firms are laser focused on returns, and their investments are transparent. They generally don’t allocate capital to speculative ventures, unproven technologies or immature industries. They look for cash-generating companies with a high likelihood of out-sized returns, making them an important window into the state of the energy transition play in the U.S.

Rapid Growth — Then a Slowdown

Looking at energy deals valued at $50 million or more, private equity deal flow in the energy transition space increased 130% per year (cumulative average growth rate or CAGR) from under $500 million in 2018 to over $25 billion in 2023. This data, provided by Pitchbook and explored in a recent article, reflects a much faster rate of growth than corporate activity, which approximated 37% CAGR over the same period.

This dramatic increase in private equity activity was an early indication that energy transition investments offered the promise of returns, and the promise of returns gave hope that capitalism could be counted on to address our climate challenges.

But then came 2024. Using the same measurement methodology, energy transition deal value involving private equity firms increased by only 7% from the prior year. By comparison, the total value of corporate energy transition deals increased by 19% over the same period.

At first glance, it might seem that private equity returns are not materializing as everyone hoped. But that could be premature. In private equity, there is a big difference between expected returns, which drive first-round investments, and realized returns, which drive second-round investments.

This is particularly true for new private equity firms entering a new investment arena like energy transition. Early investments need time to “ripen” and prove the return thesis before more money will be put to work. The dizzying early days of energy transition activity are yielding to hard work: the sine qua non of private equity success.

Reaching a Plateau

Broadly speaking, activity in energy transition in the U.S. may be hitting a plateau. The total value of energy transition deals (corporate plus private equity) increased by only 15% in 2024 to under $100 billion. In traditional energy, deal volume increased by 32% in 2024 to over $575 billion, largely due to refinancing in an improved interest rate environment. But refinancings were plentiful in energy transition, too. With growth in energy transition deal activity slowing, it may be a long time before energy transition deal volume catches up to the traditional energy space.

Importantly, the number of private equity firms investing in energy transition was also much lower in 2024 than in the previous five years. Prior to 2024, the number of new private equity firms involved in energy transition in the Pitchbook dataset outnumbered the familiar, veteran energy private equity firms by a margin of ten to one. However, over half of the private equity firms involved in energy transition in the prior five years reported no new transactions in 2024.

Newer firms with limited track records need to let their investments mature; it’s reasonable to expect a dip in deal volume after an initial burst of investment. The fact that firms with years of experience in the energy arena — like ArcLight, Apollo, BlackRock, EnCap, Riverstone and Quantum — were active in energy transition in 2024 suggests that the slowing deal volume is correlated to some extent with the newness of firms investing in energy transition. Mature energy firms with proven track records don’t need to let investments bake. Investors believe, rightly, that these firms know what they’re doing.

The data did not show private equity deal flow in energy transition shrinking. It only showed that the market is less frothy. Veterans of the energy industry will tell you that froth is not good. Hard work to produce quality returns is the stuff of long-term performance and reliability. Plenty of new firms will one day be in league with the long-time, highly successful energy private equity firms, but they’ll do it through hard work and persistence.

Which Sectors Are Driving Deals?

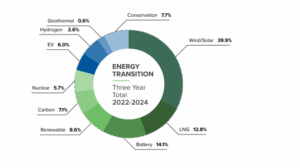

As for sectors in the energy transition space driving private equity deal activity, wind and solar remain the largest single sector, followed by battery and storage technology and liquified natural gas.

In contrast, EV-related deal activity was exceptionally low in 2024 (below 2% of total energy transition deal flow) which comes as no surprise considering the early adoption phase in the U.S. has come to an end. Private equity deal activity in carbon management, hydrogen and geothermal are also relatively low, which is not unexpected considering these sectors require substantial innovation, time to mature and scale before private equity investors move in.

Three other trends in private equity deal activity in the data set are worth noting:

- Interest in lithium deals declined, no doubt due to a collapse in the price of lithium.

- There was a noticeable shift from onshore to offshore wind deals.

- In nuclear fusion, a successful test that finally produced more energy than was consumed created new interest.

As for IRA tax credits, uncertainty around their longevity may have impacted deal volume in 2024, but the impact on private equity was muted. That’s because tax credits drive initial development, not so much buyouts of existing, cashflow-positive companies. Going forward, the curtailment of the IRA tax credit program will greatly slow new development and innovation. Ultimately, private equity may have fewer investments opportunities.

Some argue that tax incentives work against, not in support of, capitalism. If procapitalist policymakers believe market forces should drive investment, why would they support tax incentives? The answer is very simple: economies of scale. As we saw with wind, tax incentives produced investment, and investment drove economies of scale. And economies of scale produced dramatic reductions in cost per kilowatt hour. A technology that was not cost-competitive in its early days became very cost-competitive once economies of scale were achieved. Incentives can be a powerful tool in a free-market policymaker’s toolkit, as long as the incentive is withdrawn when the economies of scale have been reached.

The Stakes for US Leadership in Energy Innovation

China now dominates energy transition investing, putting more money into it in 2024 than the U.S. and Europe combined. AI is poised to drive energy demand growth, and the energy infrastructure of the U.S. is in decline. Underinvesting in energy transition increases the likelihood of energy shortages, national security concerns and a loss of our competitive edge in vital areas such as technology.

The U.S. dominated energy innovation for a century. Ceding that position of leadership at this critical time may prove to be a costly mistake. Policy makers need to get this right before the country falls behind other countries investing in energy transition. When they do, private equity should be in a good position to bundle enormous pools of capital and deploy it quickly and effectively to help solve our energy and climate challenges.

To find out more about the latest developments in private equity investments and energy transition, please contact us. We are here to help.

©2025